Ecology

The Bay Run skirts what is referred to as an estuary. Estuaries offer critical habitat for many species of animals and provide vital services such as water filtration and habitat protection from the elements, for ecosystems and organisms.

What is an estuary?

An estuary is a partially enclosed coastal body of water that is partly sea, partly river or stream and partly land. They are places of transition from saltwater to freshwater, from tidal to non-tidal, and from wet to dry. They are often called bays, lakes, lagoons, harbours, rivers or inlets.

Rodd Park, Iron Cove, Five Dock Bay, Hen and Chicken Bay, Majors Bay, Yaralla Bay and Brays Bay are some examples of local estuaries within the City of Canada Bay.

The Parramatta River estuary hosts some unique ecosystems. Read more about each of them below.

If you would like to get involved in protecting these ecosystems, join Council's bushare group.

The Grey mangrove (Avicennia marina) is the most common and widespread mangrove found along the Bay run and along the foreshore of the City. With predicted increases in storm surge intensity and rising sea levels associated with climate change, mangroves will become increasingly important in protecting our foreshores.

How mangroves adapt to their environment

Grey mangroves are a natural ecosystem that occupy the intertidal zone between the shallows of the sandy soils and the river. They can grow up to 25 metres high, though trees between 5 to 10 metres are common along the Bay Run. Trees have a large trunk covered by light grey, finely fissured bark that supports a spreading leafy crown. The leaves of the grey mangroves are glossy green with a hairy grey underside, where you will find the pores (stomata) and salt glands. Mangrove flowers are small, pale yellow blooms that grow in clusters.

A key feature of the Grey mangroves is their peg-like roots called the pneumatophores. These are spongy, pencil-like roots that spread from the base of the trunk and grow vertically through the soil surface to enable the mangrove roots to breathe.

Mangroves have adapted to survive in extreme saline soil, which is waterlogged and has a lack of oxygen. The pneumatophores act like a snorkel and enable the plants to gain oxygen. Salt is secreted through small glands on the leaf, and rain or dew wash this back into the environment.

Unlike most seeds, mangrove seeds germinate while still attached to the tree – it’s a clever way to ensure they establish quickly when they settle in the ground.

Why mangroves matter

In the past, mangroves have been undervalued and often regarded as swampy wasteland. However, mangroves play an essential role in our local environment. Some of the environmental benefits include:

- Helping to maintain aquatic ecosystem health

- Providing sanctuary for developing juvenile fish which in turn feed bigger fish

- Acting as coastal kidneys filtering sediment and pollutants from the water

- Buffering strong tides and helping to prevent erosion

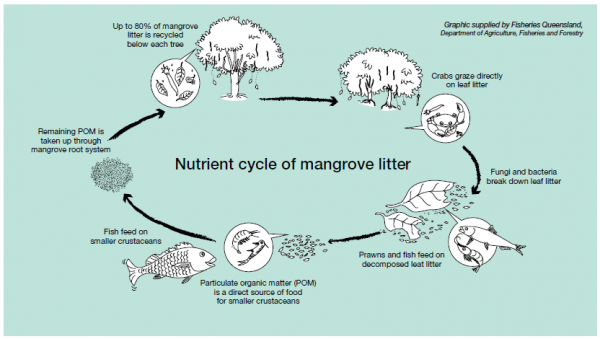

- Breaking down particulate matter and providing food for many aquatic fish and other marine life as part of the nutrient cycle.

Threats to mangroves

Mangroves are a protected species under NSW Department of Primary Industries (Fisheries) legislation. Vandalism of mangroves has been an ongoing problem in the City of Canada Bay. Both community members and Bushcare staff monitor and care for the various stands in the area. Types of vandalism include pruning, removal, cutting and destruction of mangroves. Other major threats to mangroves include:

- Marine pollution from sewage systems and drains

- Reclamation for development

- Shore protection works

- Changes to freshwater and tidal flows and drainage to reclaim land

- Uncontrolled stock access to saltmarsh/mangrove communities

- Off-road vehicles and pedestrian traffic

- Litter

- Weed invasion.

How to protect mangroves

- Do not enter mangrove areas and don’t let your pets play in them

- Dispose of litter in public litter bins

- Dispose of oils or other chemicals, including fertilisers, in the correct manner

- Report activities that damage mangrove areas to Council on 9911 6555.

Coastal saltmarsh is a community of low shrubs, sedges, rushes, reeds, succulent herbs and grasses that are tolerant of high soil salinity and are able to withstand inundation by coastal tide. Saltmarsh communities thrive on sheltered muddy foreshores of coastal lakes and estuaries often accompanied by mangroves. They can occupy narrow strips of land on steeper fringes of tidal waters or vast plains across hundreds of metres comprising different saltmarsh species located many kilometres inland.

Why is coastal saltmarsh important?

Coastal saltmarshes have been undervalued and perceived as dirty swamps full of litter, which gets stuck amongst the low plants from slowly moving tidal waters. As a result, many saltmarsh fields have been drained and reclaimed for urban development over the past 200 years.

More recent research has proved saltmarsh to have high ecological value by fulfilling important functions:

- They provide important habitat and food sources for many fauna species. High tides provide refuge and food to small fish and crabs. Adult fish use shallow saltmarsh areas to lay eggs. Low tides host wading shorebirds, some mammals or even bats who feed on insects and molluscs.

- Saltmarsh areas also improve the quality of water and catch nutrients as the outgoing tidal water slowly filters through the dense vegetation and soft soil.

- The size of saltmarsh areas and their ability to soak up tides protect coastal areas from erosion of our coast.

- Saltmarsh communities are an important carbon sink. The muddy areas absorb decaying leaves and other organic material from surrounding trees and other vegetation. The high salinity of saltmarshes prevents bacteria from decomposing this carbon, which becomes literally trapped in saltmarsh. This is known as ‘blue carbon’. Some of the carbon stored in saltmarshes has been stored in these areas for thousands of years. If saltmarsh area is disturbed, this stored carbon is being released into the atmosphere as a greenhouse gas and contributes to climate change. Preserving existing and creating new wetlands is crucial as we race towards mitigating climate change as wetlands absorb and store carbon at a rate up to 40 times faster than rainforests.

Threats to coastal saltmarsh

Saltmarsh communities have been neglected and in severe decline in the past 200 years due to causes such as:

- Land reclamation for urban development

- Tidal barriers or drainage aimed at mitigating floods

- Altered tidal flows, rising sea level and rising temperatures caused by climate change

- Mangrove or weed invasion

- Stormwater runoff

- Unrestricted stock, human and pet access

- Dumping of rubbish, litter and water pollution

- Illegal harvesting for trade or human consumption.

Local saltmarsh species in the City of Canada Bay:

- Samphire (Sarcocornia quinqueflora)

- Pigface (Carpobrotus glaucescens)

- Seablite (Suaeda australis)

- Zoysia macrantha

- Sporobolus virginicus

How to protect saltmarsh

Saltmarsh in the Sydney Basin area is listed as an Endangered Ecological Community under the Threatened Species Conservation Act 1995.

- Put all rubbish in the bin to prevent litter from reaching saltmarsh through our waterways

- Keep your dog on leash and out of saltmarsh communities, always pick up after your dog

- Do not enter saltmarsh communities

- Prevent lawn clippings from reaching saltmarsh areas to prevent the spread of weeds

- Dispose of oils or other chemicals, including fertilisers, in the correct manner

- Keep stormwater out of saltmarsh

- Join Council’s saltmarsh regeneration group

- Report activities harming saltmarsh by contacting the OEH Environment Hotline on 131 555.

Bar-tailed Godwits (Limosa Iapponica) are large migratory waders who travel from the northern hemisphere to Australian shores and sometimes as far as New Zealand every year. They are current record holders of the longest non-stop flight of 11,000 km in eight days at the average speed of 50 km/h. The Godwits lose up to half of their body weight during their exhausting journey.

These birds can be seen in City of Canada Bay estuaries and beaches from August until May. Once they have fed well and are strong enough, they set on their flight back north (Scandinavia, northern Asia or Alaska) to breed. Non-breeding adults or young birds remain in Australia all year round.

Being social birds, Bar-tailed Godwits can often be seen in groups and even mingled with other wading species. When watching Bar-tailed Godwits, observe a long and slightly upturned bill developed to look for food in soft muddy shore areas where they feed on molluscs, worms and aquatic insects.

Threats to Bar-tailed Godwits

Bar-tailed Godwits are listed as endangered species, therefore having reliable and safe feeding grounds to gather energy and sustain long flights is vital to their survival. Threats include:

- Habitat loss by land clearing for urban and industrial development or by changing tidal patterns

- Habitat degradation by weed invasion, litter or chemical pollution of feeding habitat

- Off-leash dogs that disrupt or contaminate feeding sites

- Disturbance from human activities such as recreation or fishing.

How to protect Bar-tailed Godwits

The best way to protect any wildlife, including migratory shorebirds such as Bar-tailed Godwits, is to not disturb them when you spot them and protect their habitat and feeding grounds. Bar-tailed Godwits feed on local mudflats, estuaries and bays. Godwits have also been occasionally seen in saltmarsh areas. It is important to provide these birds space to forage and feed by:

- Not entering their foraging areas

- Keeping your dogs on leash and not allowing them to run around the birds

- Disposing of litter in public litter bins.